The Invisible Plastic Problem: What Airborne Particles Do to Our Lungs

New research reveals how nanoplastics in the air trigger chaotic immune responses, leaving our respiratory system defenseless.

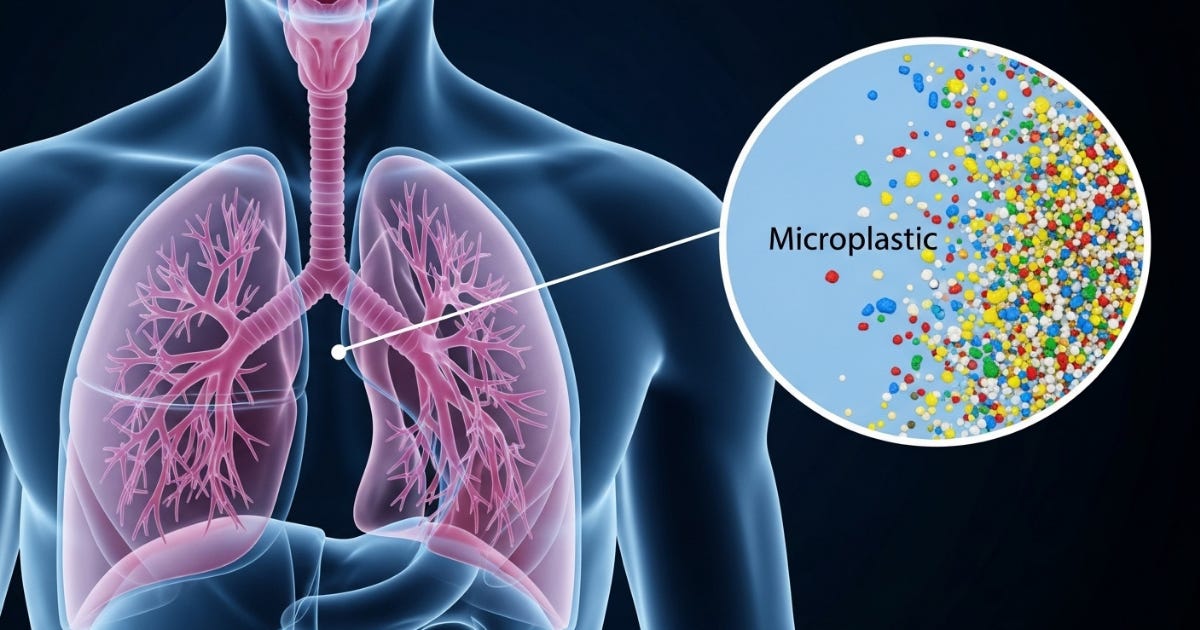

Forget about microplastics in your food for a moment. There's an even more immediate problem floating around us every day: we're breathing plastic particles so small they make microplastics look enormous.

A new study from the University of Toledo reveals that when these nanoplastics reach our lungs, they trigger what researchers describe as "disorganized and chaotic" immune responses, leaving our respiratory defenses severely compromised.

The research, published in Antioxidants (an open-access journal from MDPI), utilized donated human lung cells to simulate the effects of inhaling nanoplastics—particles smaller than 1 micron. To put that in perspective, the thickness of a human hair averages between 50 and 100 microns. Read the complete study here.

What's Happening in Our Lungs

The University of Toledo team exposed human lung cells to aerosolized polystyrene nanoparticles for just three minutes per day over a three-day period. What they found should concern anyone who breathes air regularly, which is everyone.

The nanoplastics sent those cells into overdrive, but they weren't effectively clearing the particles, akin to a car with its wipers on high but no water is being pushed off the windshield. Our lungs have specialized cells called cilia that usually sweep out pollutants and mucus. Instead of doing their job, these cells went haywire when exposed to nanoplastics.

The immune response was equally confused. "The presence of these nanoplastics seemed to confuse the cells," said Haller, who is an associate professor of medicine. "The cilia are hyperactive, but they aren't clearing anything. Inflammatory responses and immune responses need to be coordinated, but what we saw was very uncoordinated."

Where Do These Particles Come From

Every piece of plastic waste eventually breaks down into airborne particles. "As this plastic waste ages, gets battered by lake currents and is exposed to UV radiation, it starts to break down into smaller and smaller pieces," explains Dr. David Kennedy, who led the research.

The sources are everywhere: synthetic clothing releases fibers when washed, plastic packaging breaks down over time, and tire wear creates particles that become airborne. Even that reusable water bottle sitting on your desk is slowly shedding microscopic particles into the air around you.

Research shows that textiles alone contribute significantly to atmospheric microplastics, with each garment potentially releasing around 1,900 fibers per wash. These fibers don't just disappear—they become part of the air we breathe indoors and outdoors.

The Double Threat: Nanoplastics as Chemical Carriers

The Toledo study reveals something particularly troubling: these plastic particles can carry other toxins directly into our lungs. "We know that plastics, especially really small plastics, can be carriers for other things," Haller said. "You have the plastic creating a confused immune response while a toxin is also present."

This turns nanoplastics into delivery vehicles for whatever chemicals they pick up along the way. Think about it—plastic particles floating through polluted air, accumulating pesticides, industrial chemicals, and other toxins, then carrying this chemical cocktail directly into our respiratory system, where our confused immune cells can't effectively clear them out.

The researchers are particularly concerned about the potential interaction between nanoplastics and toxins from harmful algal blooms; however, the principle applies to any chemical contamination these particles may encounter.

Why This Matters More Than We Realized

Industrial workers have long demonstrated that inhaling plastic particles can cause serious health problems. "Flock workers' lung" is an occupational interstitial lung disease (pulmonary fibrosis) caused by the inhalation of flock fibers, typically comprising rotary-cut polyamide (nylon), and the inhalation of synthetic fibers has been linked to respiratory lesions and chronic bronchitis.

The difference now is that we're all effectively "workers" in a plastic-saturated environment. While environmental concentrations are lower than occupational exposures, the precautionary principle advises that this does not absolve the chronic inhalation of airborne fibrous MPs from any health risk.

What makes the Toledo research particularly significant is that it used actual human lung cells rather than laboratory cell lines, providing a more realistic picture of how our bodies respond to inhaled plastic particles.

Your Choices Actually Make a Difference

Skip that plastic water bottle today, and it won't be breaking down into airborne particles that we all have to breathe in a few years. Grab your glass containers for grocery shopping or opt for a cotton shirt instead of polyester, and you'll reduce the amount of plastic that ends up floating around in the air.

The stuff in your closet matters more than you might think. Your washing machine turns synthetic clothing into a microplastic distribution system. Every load with polyester workout gear or synthetic leggings sends thousands of plastic fibers into the water system, where they eventually become airborne.

Those fancy "moisture-wicking" fabrics that cost extra? They're just plastic marketed as performance gear, and they shed particles every single wash. Switching to cotton, wool, and linen means your laundry routine stops adding to the plastic particle problem that affects everyone's air quality.

The Bigger Picture: A Systemic Problem

The Toledo researchers note that nanoplastics are widespread both within and outside bodies of water. More than 20 million pounds of plastic waste accumulates in the Great Lakes every year, and this is just one region. The breakdown of plastic in our environment creates a continuous source of airborne particles that we can't escape.

"This is early research, but I think it helps people understand plastic pollution isn't just an environmental threat. It's a human health threat, too," Kennedy said.

The study demonstrates that the response of our respiratory system to nanoplastics is fundamentally different from its response to natural particles, and not in a beneficial way.

What We Can Do Right Now

While we can't altogether avoid breathing airborne plastics, we can reduce their concentration in our environment:

Choose natural materials: Opt for clothing made from cotton, wool, and linen instead of synthetic fabrics that shed microfibers.

Reduce single-use plastics: Every plastic bottle, container, and piece of packaging eventually breaks down into microplastics, which can be inhaled as airborne particles.

Support policy changes: Advocate for regulations that address plastic pollution at its source rather than just cleanup efforts.

Use alternatives: Glass containers, stainless steel bottles, and natural fiber products all help reduce the overall plastic load in our environment.

Bottom Line

The research confirms what environmental advocates have been warning: plastic pollution isn't just an "environmental" issue, it's a direct threat to human health that we're breathing in every day. The particles are so small that we can't see them, but our lung cells can detect them.

The convenience of single-use plastic comes with a hidden cost. That disposable coffee cup, the plastic utensils from takeout, the single-use water bottles, they all eventually break down into particles that become part of the air everyone breathes.

The good news is that switching to reusable alternatives makes a significant difference, not only in reducing waste but also in improving air quality.